NBA Legend Dikembe Mutombo Rejects the Status Quo of Surgical Care in the DRC

Surgical care in the DRC is a grim picture, but the Dikembe Mutombo Foundation has set out to change that.

Surgical care in the DRC is a grim picture, but the Dikembe Mutombo Foundation has set out to change that.

Last week, Mashable published a video from an organization called Cordaid that follows a pregnant woman on her way to a maternity clinic in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The video is set in real time, so viewers have the rare opportunity to witness this journey in its entirety. Spoiler alert: it’s five hours long.

The woman, Chanceline, lives 17 miles from the nearest source of healthcare, and because there’s no transportation available to her, she has to make the trek on foot. While pregnant. Across rough terrain. Through a rainstorm. Alone.

Heartbreaking as it may be, Chanceline’s story is commonplace in the DRC. Despite being Africa’s second-largest country by land area and fourth-largest by population, the DRC ranks among the worst when it comes to health and wellbeing. Congolese women have a one in 24 chance of dying during childbirth, with many more suffering debilitating injuries. Every tenth child dies before her fifth birthday, and of those, one in three fails to live past her first month. Unsurprisingly, the country’s average life expectancy ranks 206th in the world. It seems almost tragically fitting that two of the world’s most well-known and insidious viruses —Ebola and HIV — are believed to have originated in this embattled central African country.

It was against this sobering backdrop that NBA Hall-of-Famer and DRC-native Dikembe Mutombo set out to pivot his post-basketball energy toward improving life in his home country. In 1997, he started a foundation with the mission of improving health, education and overall quality of life for the Congolese people. A decade later — in the twilight of his playing career — he constructed the Biamba Marie Mutombo Hospital in Kinshasa, the capital city — creating a state-of-the-art facility that has become a bastion of high-quality care in the region and a valuable source of employment and education. Since then, the hospital has transformed health services for hundreds of thousands of local patients, and it recently completed an effort to bolster its capacity to perform safe surgery.

Surgical care in the DRC is a grim picture to say the least. As Chanceline’s journey illuminates, health facilities are already few and quite literally far between, and even among those that do exist, most lack the infrastructure and expertise to provide surgery. Last year, the World Health Organization conducted an analysis of a dozen district hospitals in the DRC and found that nine had unreliable or no running water, seven had unreliable or no electricity and eight had no functioning anesthesia machine. Another study revealed that the country has the fewest anesthesia providers per capita — one for every five million people — which drastically limits its ability to deliver surgical care.

Had Chanceline experienced a pregnancy complication on her journey, she would have been a full day’s walk from the nearest hospital that could treat her (Panzi Hospital in Bukavu — 56 miles away). And if she didn’t make it, she would have been stranded on the road, her life and that of her baby hanging in the balance.

Mutombo knew these circumstances all too well when he decided to make surgery a priority for his foundation. Just after visiting the Mutombo Hospital earlier this week, he acknowledged, “We can’t afford to focus on a single health challenge anymore — we must build a system to treat any issue that arises, and surgery helps us do that.”

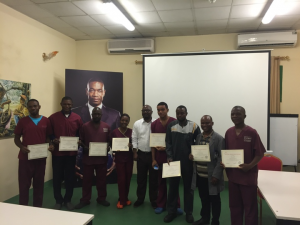

As part of this commitment, Mutombo’s foundation partnered with my organization to improve surgical capacity at his hospital. After installing an anesthesia machine and hosting a training for its staff, the hospital will now serve as a regional training center for anesthesia providers and biomedical technicians across the country, ensuring that providers are able to deliver anesthesia appropriately and technicians are able to maintain medical equipment effectively and efficiently. The impact of this investment is sure to be both significant and long-lasting.

With its new machine and commitment to training, the hospital has expanded its ability to perform surgery (as shown in this recent Facebook post from the foundation), and more and more local Congolese patients are receiving the care they need. Among the many people working to make this possibility a reality, a certain basketball legend stands out in particular. But it’s not because his body spans seven feet from head to toe and he rejects basketball shots; it’s because his heart spans seven thousand miles from Atlanta to Kinshasa and he rejects the status quo.